Move over, Ninja Turtles—there’s a new hard-shelled, talkative superhero in the city sewer system. Meet SIM (Sewer Inlet Monitor), defender of our rivers and streams, guardian against street flooding, and unrepentant tattletale. SIM texts or emails when sewer inlets become clogged with trash, alerting the public when cleaning is needed.

Yesterday, five 10th-grade students from Mariana Bracetti Academy Charter School presented SIM at the regional portion of the 2016 Governor’s STEM Competition. At the School District of Philadelphia, judges from the Mayor’s Office of Education and Drexel University awarded the students first prize; they will advance to the statewide competition in May to represent Philadelphia. (Full disclosure: They faced no competition from other teams. Full disclosure, Part II: These students worked after school, they came into school on days off, they worked after full days of standardized testing, so … they won and they earned it.)

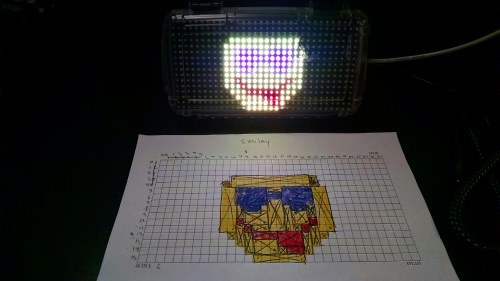

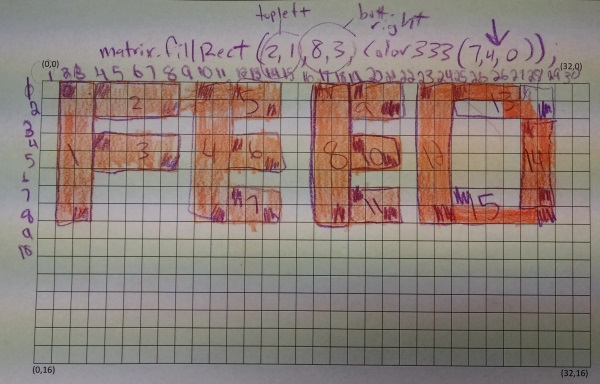

The photo above shows SIM on the outside; it’s camouflaged, waterproof, and rugged enough for, well, a sewer inlet. The device’s inner workings are, for now, a trade secret. (We’ll open-source the project shortly after the state competition.) The Mariana Bracetti students worked with Philadelphia Water‘s greenSTEM project to research a community problem (excessive trash near the school, right across the street from Frankford Creek), learn basic coding and circuit-building, develop a prototype, test, and revise the final product.

In addition to presenting SIM to the judges and conducting a succesful live demo, the students were issued a Project in a Box challenge: given 30 minutes and a mystery box of materials, they had to work as a team to solve a problem. The challenge? Build a paper airplane to fly a raw egg into the center of a target, using a short list of materials (tape, tissue paper, glue, etc.). Here’s how it went:

Submit your egg jokes/puns in the comments section.

Thanks to the School District and the judges, as well as Mariana Bracetti teacher Lauren DeHart and Drexel/greenSTEM coding mentor Sean Force.