Rain Barrel to Inbox: I’m Full

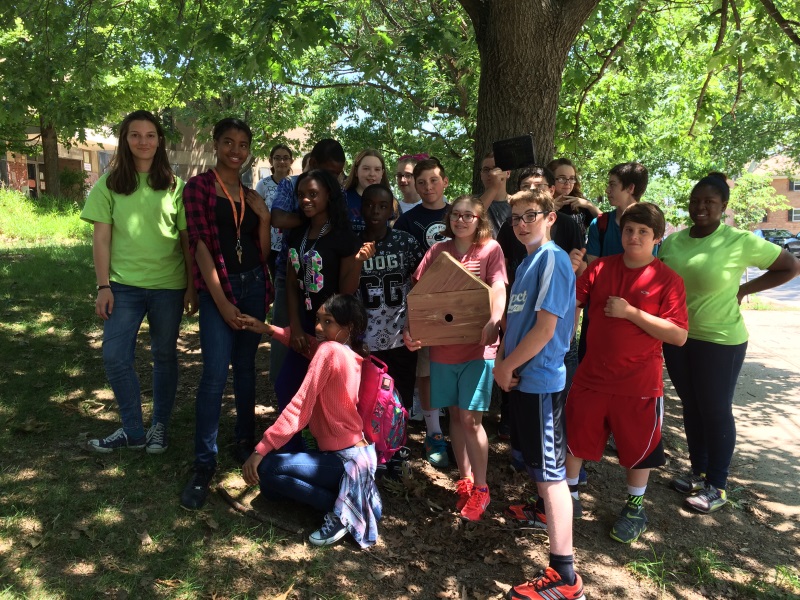

The next generation of scientists and engineers at Philadelphia’s Penn Alexander School are developing the next generation of rain barrels. The rain barrel, of course, is a staple of the Philadelphia Water Department’s Rain Check program, aimed at enabling residents to manage stormwater and prevent pollution from entering our rivers and streams.

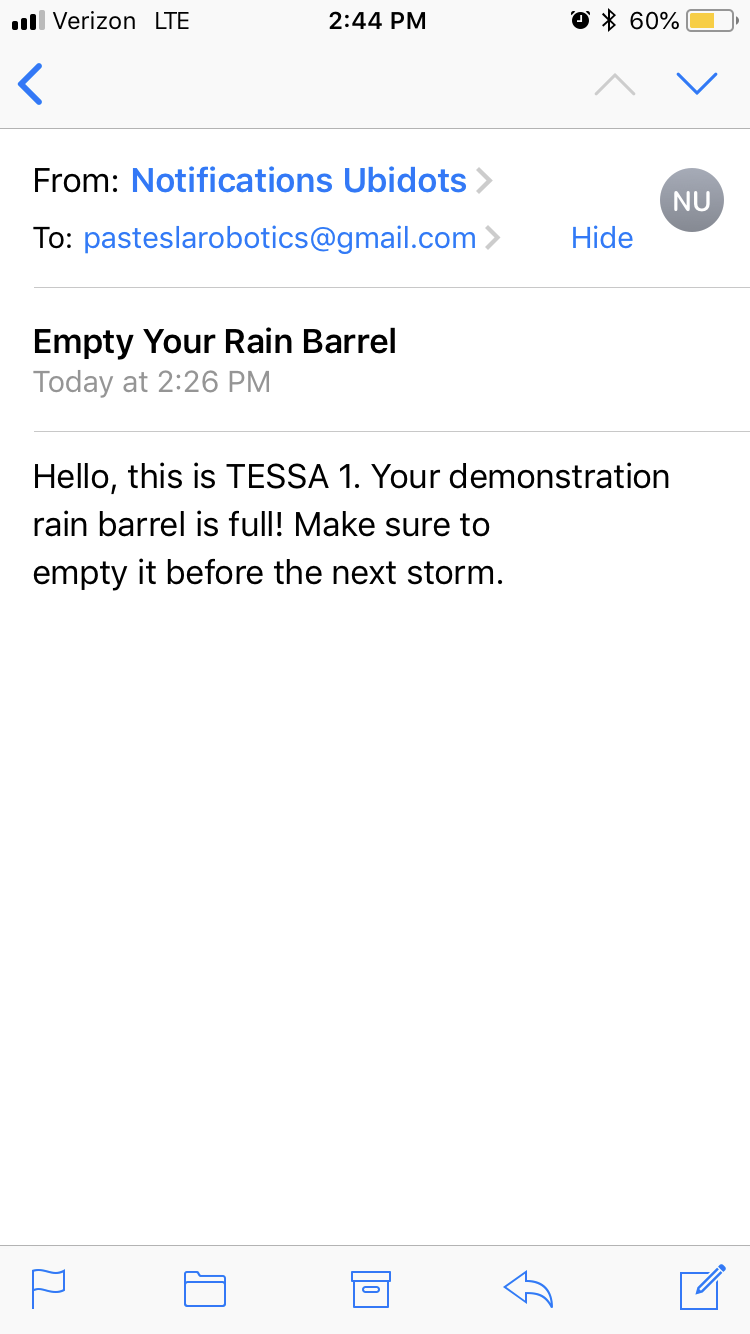

PAS Tesla Robotics, a group of middle-school students who convened last year to compete in the FIRST Lego League competition, decided to take on an issue that affects the approximately 3,500 Philadelphians who own rain barrels: How do you ensure that residents empty their rain barrels before a storm? And how can we know that the barrels are effectively capturing water? The students invented Tessa, a smart, sensor-enabled rain barrel that can send a text or email to let people know when the rain barrel is full. In order to accomplish this high-tech feat, the group researched sensor technology and microcontrollers, learned to code in C++, and set up a cloud data service to send rain barrel notifications straight to a cell phone.

This week, PAS Tesla Robotics demonstrated Tessa to PWD, the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, Drexel University and engineering firm AECOM; they expertly explained Philadelphia’s combined sewer overflow problem and the need for effective rain barrel management. The students are honing their presentation for the FIRST world championship in Detroit later this month. (Did we mention the team already won local and state competitions?) The live demo included a successful email notification from the test barrel when the barrel sensed it was full. And, of course, the team has already identified several improvements to the device, such as a more accurate sensor and incorporation of weather forecast data—stay tuned. Best of luck to Tessa and PAS Tesla Robotics in Detroit!