With the installation of sensors at four Philadelphia schools about a month away, it was time to build some additional Root Kits. Version 1.0 is housed in a Pelican 1010, a $10 waterproof case normally used for stashing your cell phone during whitewater rafting trips or something. We used a half-inch drill bit to drill out the three holes for the soil moisture sensor cables, and the cables are secured to the case with PG7 cable glands (about $3 for a pack of 10) that you can tighten by hand.

A few words about drilling: This was a two-person job; one person steadying the left side of the case and the other drilling, slowly and with constant pressure, the three holes. At first, we experimented with drilling pilot holes with smaller bits and moving up to the half-inch bit, but by the end we just did the job with the half-inch bit from start to finish. (We haven’t yet cracked the plastic on the Pelican cases, but have definitely destroyed a variety of less-sturdy plastic components while drilling.) It was difficult to align the holes and make it look pretty. The drill bit walks. This is not of great concern, however, since these cases will eventually be covered by students’ creative and artistic designs.

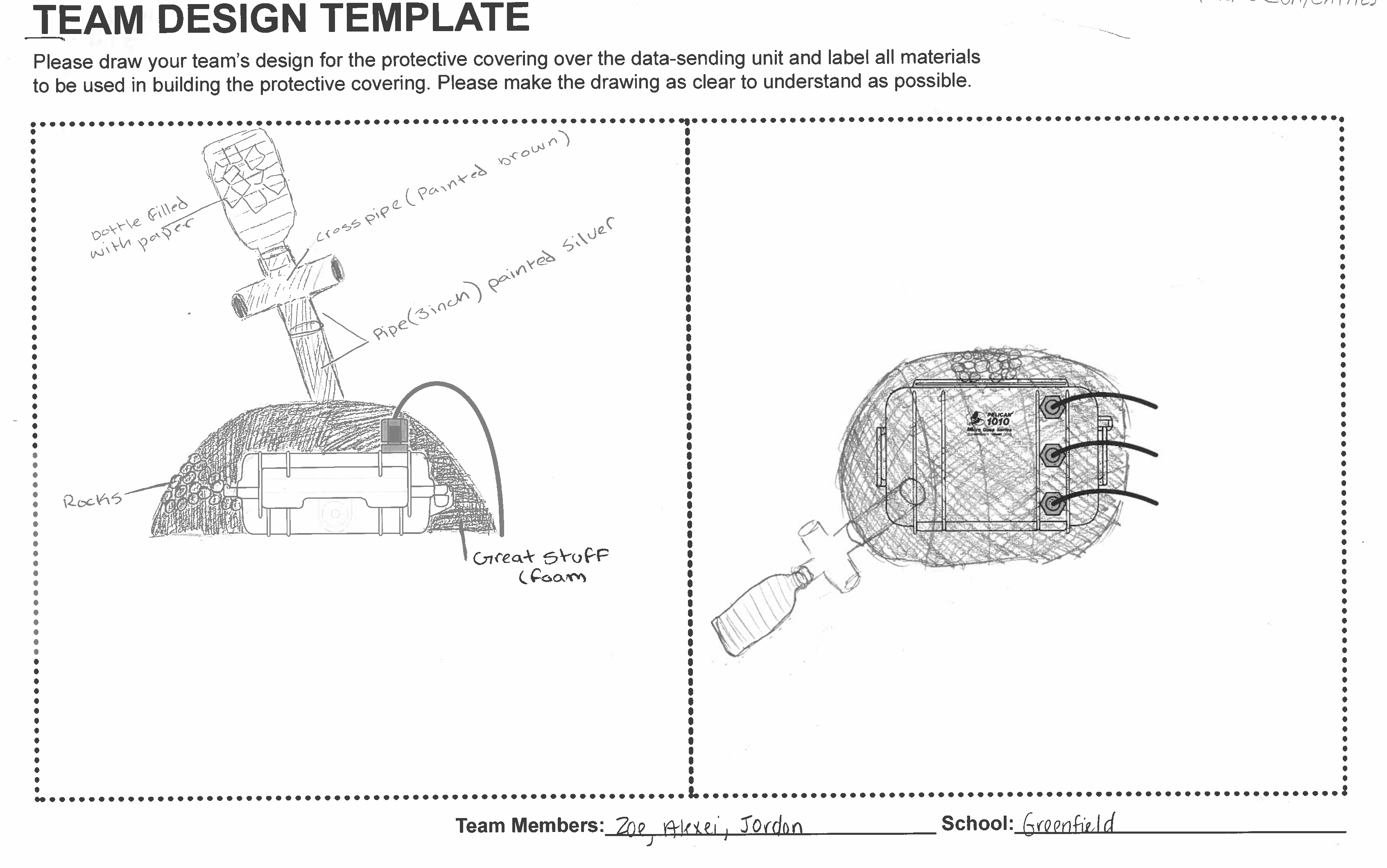

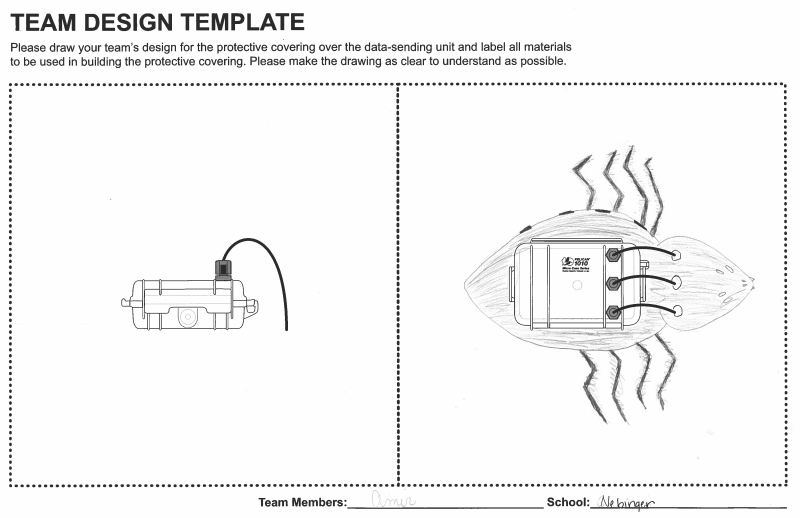

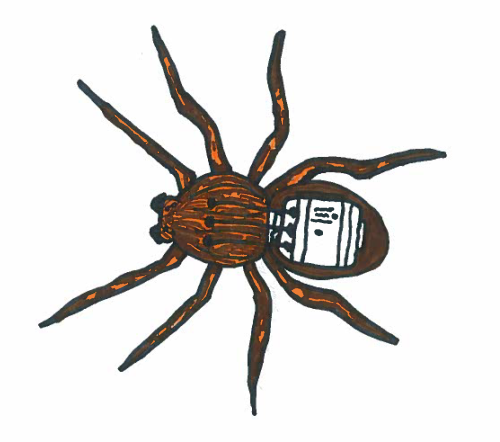

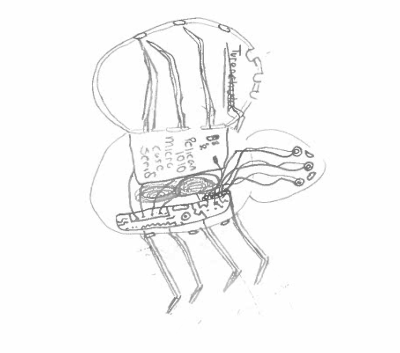

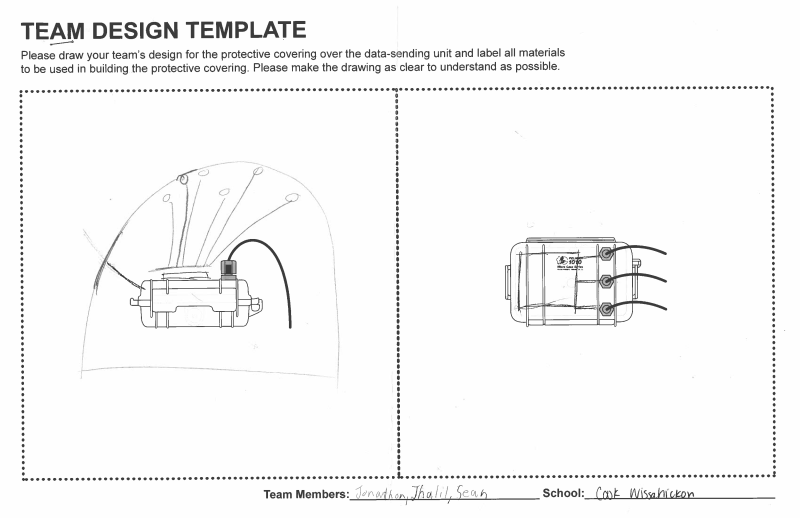

Speaking of which, students at Greenfield, Nebinger, and Cook-Wissahickon elementary schools are currently designing Root Kit housings for the design competition. The deadline for submissions is April 4, and more info and downloadable packets and drawing templates are here.

We’re in the process of assembling a complete set of instructions for assembling the Root Kit and plan to work with students at Science Leadership Academy’s Beeber campus this spring to be the first large-scale manufacturers of these sensor kits.