Smart Green Roof Project: Chapter 3

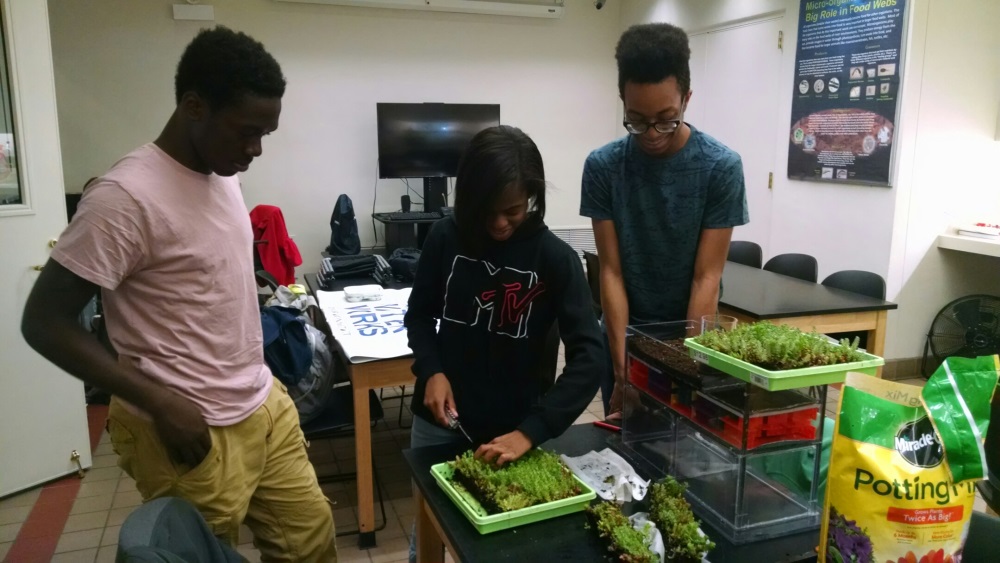

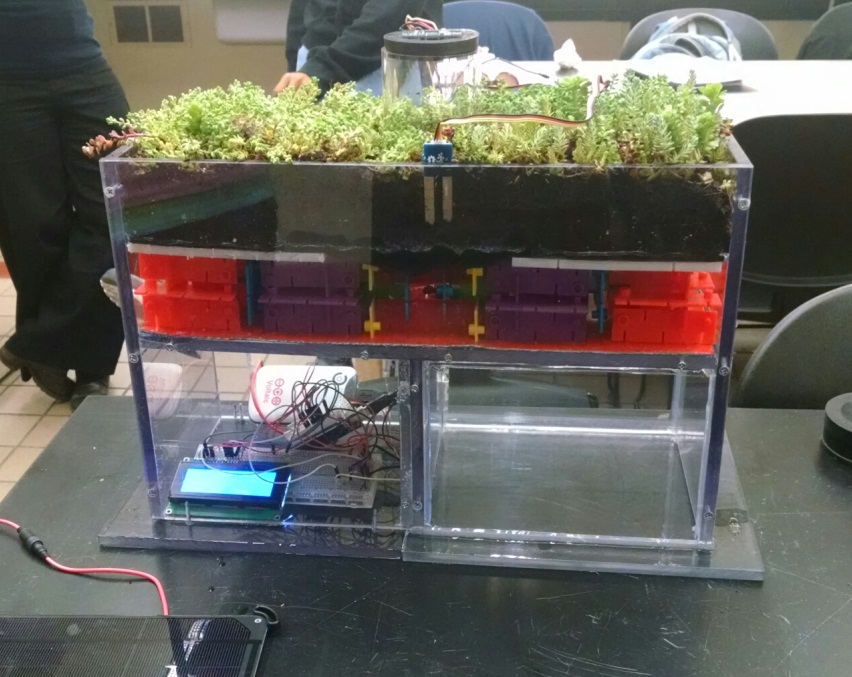

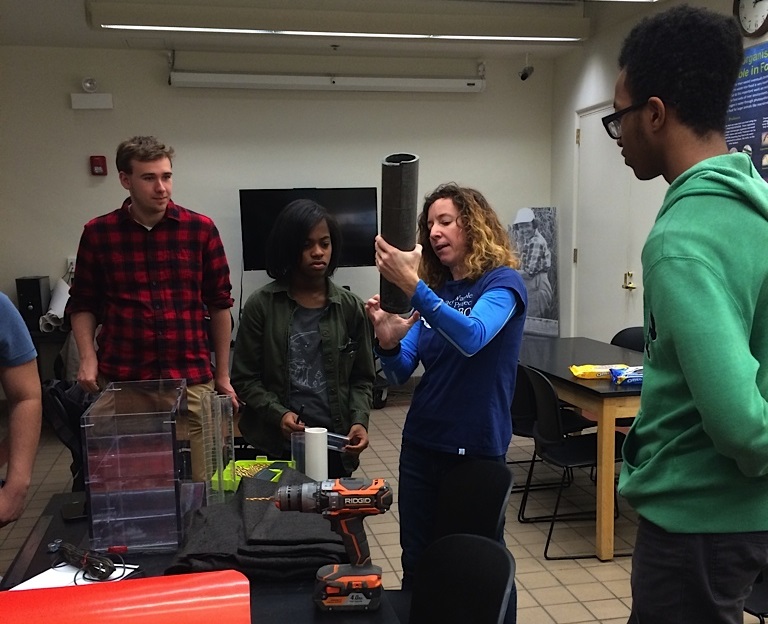

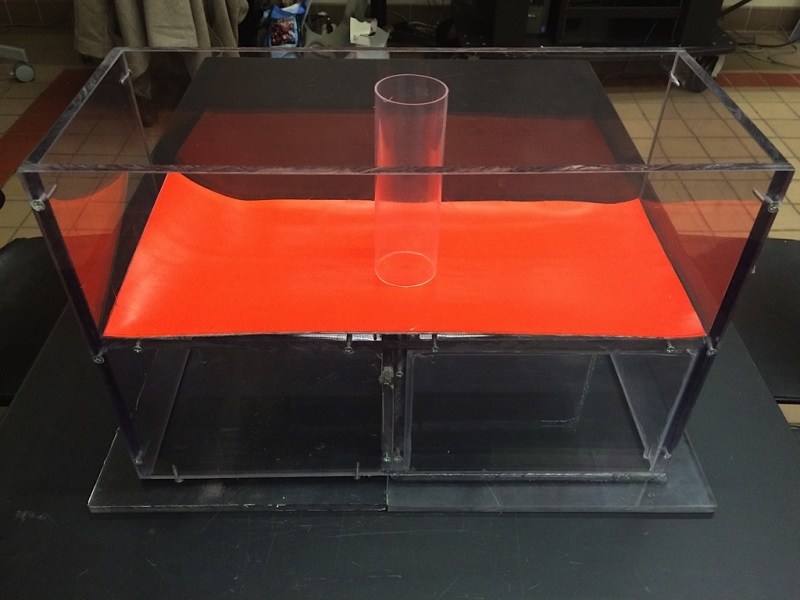

The roof has grown—SLA Beeber students wrapped up version 1.0 of their Smart Green Roof model at the Fairmount Water Works this month, completing the project by creating the storage layer and planting sedum. The storage layer—made of brightly colored plastic pieces beneath the soil (constructed from Locktagon toys)—is designed to hold water as it seeps through the soil and through a filter fabric.

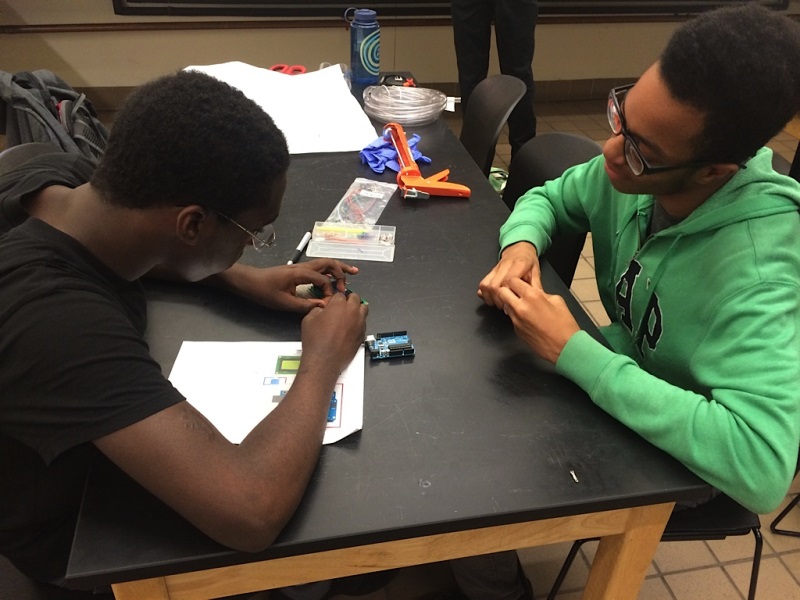

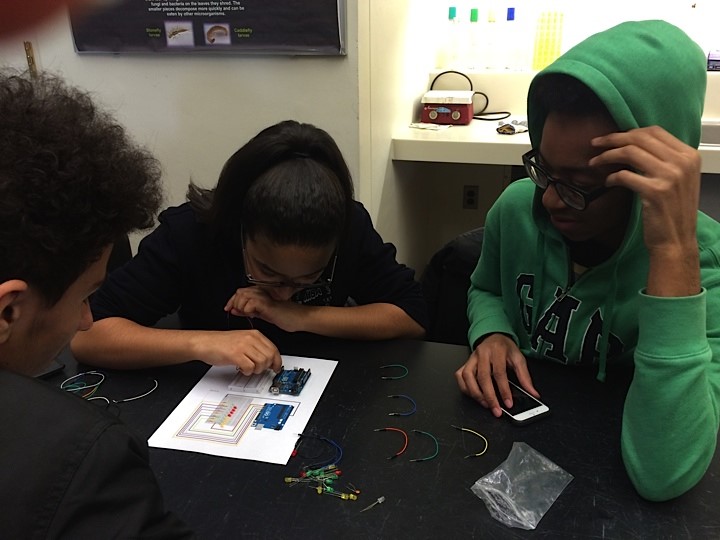

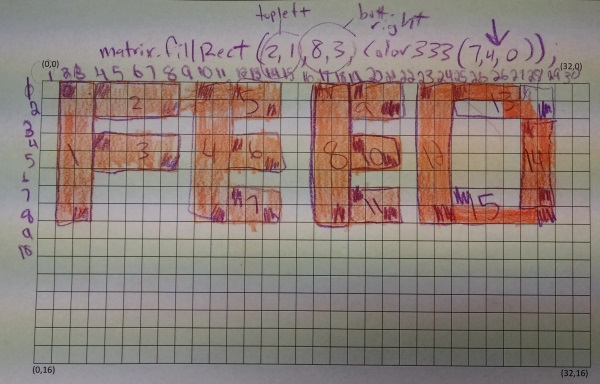

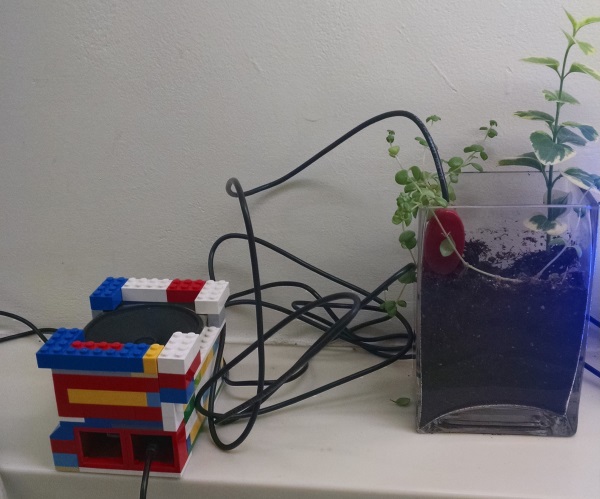

What makes this a “smart” model are the sensors designed to monitor how this miniature green roof uses and stores water. Soil moisture sensors and a temperature sensor can inform us about plant health; and an ultrasonic distance sensor looks down an observation well to gauge the level of water in the storage portion of the model. The data can be seen on an LCD display, and all of it is powered by a solar panel. The empty compartment in the lower right part of the model will someday house a pump that can irrigate the plants on demand. (That’s version 2.0 of the model.)

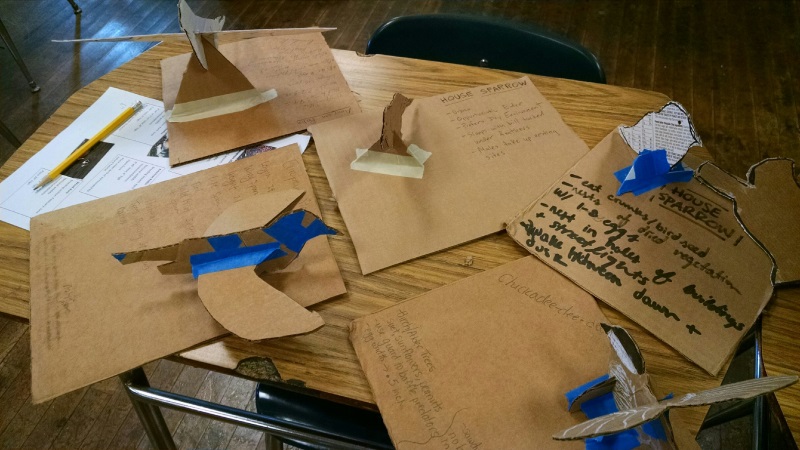

In April, the Smart Green Roof team brought the model to the Philadelphia Science Festival, where we demonstrated how green roofs work and what they do: capture stormwater, reduce the urban heat island effect, and save energy by insulating buildings.

This week, we finished with a trip to Villanova University to check out the green roof on top of the college’s CEER building. Because Villanova researchers have also outfitted their green roof with a variety of sensors and irrigation devices, it is very much like a scaled-up version of the Smart Green Roof model.